The Ecphorizer

|

|||

|

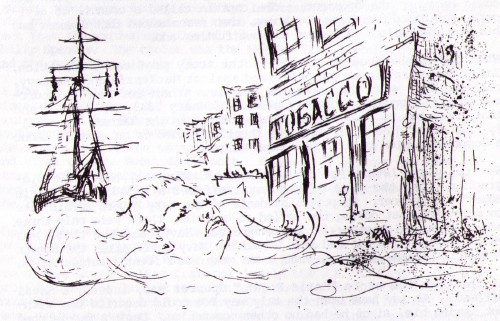

Murder, mutiny and the Killer Sotweed In July of 1841, a scandal struck New York. The corpse of one Mary Rogers, her face blackened by strangulation, was found floating near the New Jersey shore of the Hudson River. She had been employed as a salesgirl in Anderson's cigar store on lower Broadway. It was considered scandalous for a young lady to wait on an all-male clientele, which is all there was in cigar [quoteright]stores. Anderson had banked on the scandalousness of the arrangement, as well as Mary's good looks, to draw in crowds of customers. By all contemporary accounts, it was a sound marketing decision. Mary was a sensation when she was alive. Dead, she was even better. The city's newspapers vied with one another to churn out gory and sexually suggestive prose. Many students of American journalism date the kind they call "yellow" from the Rogers murder. But that was about all that came of it. Her killer was never apprehended. There was quite a bit of speculation. The most famous piece was written by Edgar Allen Poe, "The mystery of Marie Roget," in which the Rogers murder was transposed to Paris and the cast of characters all received Gallicized versions of their real names. Poe's detective, M. Dupin, concluded, from inferential reasoning, that the murderer was a naval officer - but he offered no further details. Poe had done original field-research on the story in New York, but he never published any evidence that he may have found there. About a year and a half after the Rogers murder, the brig U.S.S. Somers was returning from a training cruise to the west coast of Africa. Somewhere near the Virgin Islands, the crew was assembled on deck. A lengthy order was read by the First Lieutenant, and then, on a signal from him, a cannon boomed, and three men were hauled up to hang by the neck from the yard-arms. One of them was a young naval officer named Philip Spencer. The cruise was the Navy's first training cruise ever, and the execution was the first in the Navy's history for mutiny. It was a peculiar voyage in a number of respects. With few exceptions, the officers were relatives of Commodore Matthew Perry and his brother-in-law, John Slidell, leading lights of the Northern and Southern wings of the Democratic Party, respectively. The First Lieutenant, one of the exceptions, was Herman Melville's close friend and first cousin, Guert Gansevoort. Midshipman Spencer had been the other notable exception. Not only was Spencer a Whig - his father, John Canfield Spencer, was at that time serving as Secretary of War in the Tyler Administration. Philip Spencer had spent almost four years in the freshman class at two different colleges. He had frittered away his time at everything but his studies; in his fourth year as a freshman, he organized one of the oldest Greek-letter fraternities in the U.S., Chi Psi. Chi Psi proved to be the last straw. An infuriated John Canfield forcibly exmatriculated his son from Union College and packed him off to the Navy, which served at that time, among other things, as a dumping ground for refractory youths. He left Union College in April, 1841. In September, he went aboard the Navy's receiving-ship, U.S.S. New Hampshire, in New York. There is no documentary evidence as to his whereabouts in the interim. He was posted as a midshipman to the Brazil Squadron, where he made quite a name for himself. Where Philip Spencer had been a wastrel before, he now became a menace. He drank and smoked to excess. He shunned his fellow officers and fraternized with the seamen. Ashore in South America, he brawled with an English midshipman. He was sent home in disgrace. Perry had just talked the Navy brass into instituting training cruises. ground for refractory youths. He left Union College in April, 1841. In September, he went aboard the Navy's receiving-ship, U.S.S. New Hampshire, in New York. There is no documentary evidence as to his whereabouts in the interim. He was posted as a midshipman to the Brazil Squadron, where he made quite a name for himself. Where Philip Spencer had been a wastrel before, he now became a menace. He drank and smoked to excess. He shunned his fellow officers and fraternized with the seamen. Ashore in South America, he brawled with an English midshipman. He was sent home in disgrace. Perry had just talked the Navy brass into instituting training cruises. Somers, which had just been commissioned, was chosen as a vessel for the first one. Perry packed it with people he felt he could count on to make it a success, mostly relatives. When Spencer showed up on U.S.S. John Adams, Perry assigned him to Somers, thinking that the cruise might help straighten him out. The captain, Alexander MacKenzie, refused to take Spencer, his reputation having preceded him. Perry overruled MacKenzie. Spencer was, if anything, ever worse aboard Somers. And on the return leg of the cruise, on 1 December 1842, he approached the steward, Wales, to recruit him for a mutiny. According to Wales, the plan was to kill the officers and loyal crew and then convert Somers to a pirate ship. Somers and her three sister ships were the fastest sailing ships on the ocean - she would have been a fearsome engine of destruction. Wales communicated the plot to Gansevoort, who alerted MacKenzie. MacKenzie had Spencer clapped into irons, along with two seamen who were his closest and most conspiratorial-looking companions. Found in Spencer's possession was a watch-list bearing out Wales' description of the plot. It was written in Greek, as if to conceal its import (fortunately, Perry's nephew, Henry Rodgers, had studied Greek and could decipher the document). The captain called a council of officers, who heard witnesses for hours, then recommended that Spencer and his two accomplices be hanged without further ado. When Somers berthed at New York, the story produced a sensation. James Fenimore Cooper pamphletized against MacKenzie and the Navy, charging them with the murder of innocents (there had been no court-martial). A court of inquiry held in January 1843, however, found that there was no cause to bring any charges in the matter. Eventually, the furor died down, although there continued to be murmurs about a Democratic plot to kill prominent Whigs. Several years later, Poe confided in W.K. Wimsatt, his first biographer, that the name of the naval officer alluded to in "Marie Roget" was Spencer. Skeptical students of the Mary Rogers affair like to point out that during the period in question, there were only three officers named Spencer in the whole U.S. Navy, and the third was Philip himself - who had not joined the Navy until after the Rogers murder. I think, however, that I can make Poe's identification stick. At the time Poe wrote "Marie Roget," Spencer was, indeed, a naval officer. It may have been the only way Poe could describe him without naming him, since he had no other occupation. Dupin's far-fetched inferences may be due to a similar desire not to give away the real reasons for the identification. There is abundant testimony to the effect that Spencer, who had been a good-natured ne'er-do-well at college, had become vicious and violent at some juncture between Union College and the US Navy. The circumstances of the publication of "Marie Roget" also support this interpretation. The story was scheduled for publication in three monthly installments, beginning in November, 1842. Hard on the heels of Somers' return to port in December, Poe recalled the third installment and furiously rewrote it. It was not resubmitted until after MacKenzie's board of inquiry had published its findings. That installment, in which Dupin advances the naval-officer theory, appeared in February. One of the facts that came out at the board hearings was the scope of Spencer's addiction to tobacco. The purser's records showed that in the three-month course of the tragic voyage, he had drawn more than seven hundred cigars from ship's stores. It does not seem far-fetched to suppose that being in disgrace, he was not welcome at home in upstate Canandaigua; as he was scheduled to enter the Navy in New York anyway, it seems reasonable to suppose that he spent the summer of 1841 in New York with his Navy uncle, who might well have been pulling strings to get his nephew a good berth. In that case, there is no more likely place to look for a well-to-do young layabout in New York City, summer of 1841, than in Anderson's cigar store on lower Broadway, stocking up on the demon weed and taking in the charms of young Mary Rogers. Wales testified that Spencer's plan for women prisoners was to rape and then drown them. Spencer as prisoner accepted his sentence with hardly a protest. Was his projected career of rapine and murder nothing but a continuation of a course already undertaken? Did he meekly accept death as punishment for an unhatched plot, or for a dark deed already committed? The answers will probably never be known. But I think it is clear that Poe's Spencer and the mutineer of the Somers were one and the same, and that whatever evidence Poe had to go on was provided by the tobacco connection. [line width="40%"]  Illustration by Burt Schmitz

Gareth Penn hastened to send in his reservation for the Ecphorizer Gathering in November, hoping to follow his nailing of the Zodiac killer with a quick solution to "Murder at the EG." |

|||

|

Title:

E-mail

Print to PDF

Blog

Link: Summary: We have collected the essential data you need to easily include this page on your blog. Just click and copy!close |

|||